You can read this article on medium at the link below…

Articles & Interviews

Stay in Touch

Sign up for Alice’s monthly newsletter! Readers get:

- A free Austenesque short story

- Members-only info

- Updates on progress on Alice's latest book

- Discount offers

- Bonus content

Article categories

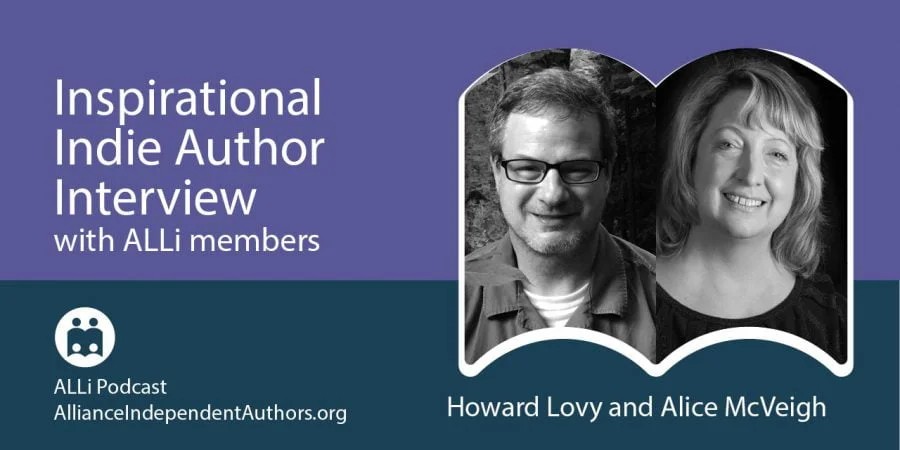

Interview: Alice McVeigh – Utterly Charming Jane Austen-inspired Fiction

You can read the interview with Naomi Bolton at Manybooks at the link below.

Interview: An ADHD Diagnosis in Her Fifties Helped Alice McVeigh Write Fiction Again

You can read the Tuesday Author Interview with Christina Boyd for the Who, What, When, Where, and Why at the link below or listen to it here.

Janeite Spotlight: Introducing Alice McVeigh

Read Sarah Hurley’s article at Jane Austen Summer Program using the link below…

The curious allure of Miss Mary Bennet

Read Alice’s article at Historia using the link below…

P English Literature Author Interview with Alice McVeigh

You can visit this podcast at the link below.

Why your friends hate your novel

You can read this article on medium at the link below…

Do you have to “root” for a protagonist?

You can read this article on medium at the link below…

How not to sell paperbacks at artisan fairs

You can read this article on medium at the link below…